Author

Bogdan Siniecki, physician, 1925–1993, contributor to Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim.

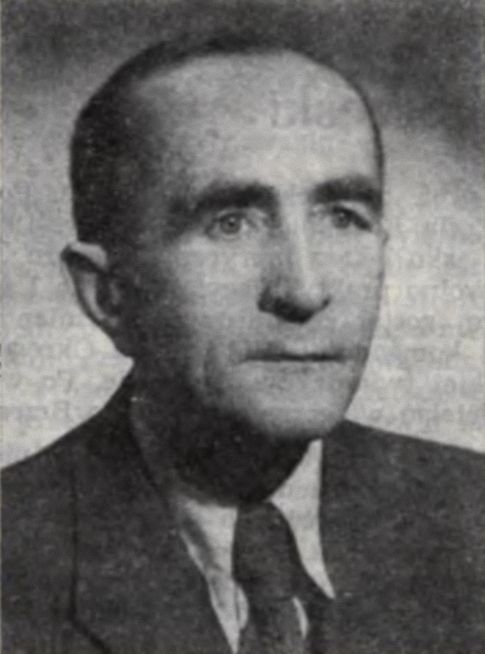

Dr Aleksander Witkowski was the only one of all the Polish doctors arrested in the Free City of Danzig (now Gdańsk)1 and sent straightaway to Stutthof concentration camp, who survived in the camp to the end of the War. In late January 1945, he was evacuated and had to go on the merciless Death March out of the camp. En route in March 1945 he was liberated by Soviet troops. Dr Witkowski’s veteran status in the camp was evidenced by his three-digit camp number: 944, low indeed if compared with the total of 120 thousand prisoners registered in Stutthof. The other Polish doctors from Danzig were either killed or died in the first years of their confinement in the camp.2 Only one of them, Dr Witold Kopczyński, was transferred from Stutthof to another camp in 1941, and thus escaped certain death there. He was set free when Dora-Buchenwald,3 the last camp in which he was detained, was liberated.

Aleksander Witkowski was born in Bydgoszcz on 25 October 1902. He attended the Städtisches Gymnasium Danzig.4 At school, he was a co-founder of a secret branch of the Association of Gdańsk Philomaths and Philareths,5 an organization promoting Polish patriotism. In 1919, when Gdańsk became a Free City, he and his schoolmates Stefan Mirau and Witold Kopczyński, who later became doctors, as well as Alf Liczmański, Wanda Marlewska, Maria Bawelska and Stefan Tejkowski, set up a secret branch of the ZHP Polish scouts’ and guides’ movement. In 1922 Aleksander Witkowski enrolled at the University of Munich for Medicine, and completed his studies in 1928. On graduating, he started work with an ophthalmology clinic in Munich and in 1929 wrote his doctoral dissertation on ophthalmology.

He returned home in 1930 and served as a medical practitioner in the Directorate of Danzig State Railways, holding the post until 1936. Until the outbreak of the War, he had a doctor’s surgery of his own in the city centre. He used to visit the Polish military garrison at Westerplatte,6 and provided medical treatment for the men stationed there.

When the War broke out on 1 September 1939, the Gestapo arrested Dr Witkowski, taking him from his apartment to the Victoriaschule and later to the transit camp in the Neufahrwasser (now Nowy Port)7 barracks. These were places where the Germans executed Polish inhabitants of Danzig. Dr Witkowski was sent to Stutthof on the first transport of prisoners, and initially had to do hard labour clearing the forest. In the evenings, after work, he took care of sick fellow inmates. In early 1940, as soon as a hospital barrack was built in the camp, Dr Witkowski was ordered to manage the surgical ward, while Dr Stefan Mirau8 managed its internal medicine ward.

Shortly afterwards, Dr Witkowski was transferred to Aussenkommando Stutthof Elbing Schichau.9 a new sub-camp in Elbing (now Elbląg), where hundreds of prisoners worked in the shipyard, producing submarine parts for the German Kriegsmarine. Here Dr Witkowski treated prisoners and established an outpatient service. In 1942–1943 he was often seen in the city centre attended by a prisoner and guard, visiting the Adler-Apotheke pharmacy to collect medications for the sub-camp. This was the only opportunity he had to contact his family and relatives. He was sent back to the main camp in 1944 and resumed his job in the hospital.

In one of his last letters to his mother Leokadia Witkowska, sent from the camp towards the end of the War, he regretted that he would miss her 70th birthday. He asked her to look after herself and not worry about him. In this letter, he sadly admitted that he had already had six birthdays in captivity.

From the first days of January 1945, the camp authorities hastily set about destroying the hospital records, and on 25 January, after dividing the entire camp into eight marching columns and distributing food for the first two days of the march (half a loaf of bread and a quarter-pound of margarine per head), they started to evacuate the prisoners. Only the seriously ill and a group of Jewish prisoners were left in the camp. Several long weeks of marching along the roads, fields and highways in the environs of Gdańsk were ahead of them. Their destination was the vicinity of Wejherowo and Lębork. Dr Witkowski was assigned to the first marching column, numbering approximately 1,600.

The journey was very hard, and after walking up to thirty kilometres a day, prisoners were on the verge of exhaustion due to hunger, sub-zero temperatures, and snowdrifts. The most exhausted prisoners went down and died on the way, many were gunned down by the SS escort. They spent the nights in sheds, stables, barracks, or churches. In early March 1945, the decimated column reached the village of Gans (now Gęś) near Lębork. Most of the prisoners went sick, suffering from particularly troublesome digestive tract diseases and diarrhoea.

One of Dr Witkowski’s fellow prisoners, Balys Sruoga,10 a Lithuanian professor who had been held in Stutthof since 1943, wrote the following account of his time in Gans and Dr Witkowski:

In the shed we were put up in at Gęś there was a doctor called Witkowski from our column, a Pole from Gdańsk, who had spent over five years in the camp. He was a good and affable man; he was so exhausted he could hardly keep up on his feet. He had no medicines or instruments because the SS did not allow him to take anything out of Stutthof. When he saw our fellow prisoners running a temperature due to typhus or paratyphoid, he just gave a sad nod and went away without a word. If he had reported it to the SS, they would have sent them straight off to the “hospital,” that is a mortuary, not a treatment facility. The sick men would have died there right away. But if they stayed with us they had a chance to survive. And fortunately no one was infected by them. Yes, Witkowski was a very good man, God bless him.

The prisoners’ ordeal came to an end when Soviet soldiers entered the sub-camp. Dr Witkowski, who had contracted typhus, was sent to their field hospital and spent six weeks there. On recovering, he returned to Sopot, and was one of the first doctors to start work in the municipal clinic. Although he was not physically and psychologically fit enough yet, he devoted all his energy to treating the people of Sopot, which had a rising population. But his health continued to deteriorate. He fell seriously ill and had to stop seeing people. The only person who was sincerely devoted to him in these difficult, last days of his life was his sister Jadwiga. She was with him to the end: he died on 10 November 1973.

Notes

- From 1920 to 1939 the Free City of Danzig was a semi-autonomous city-state consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig and nearly 200 towns and villages in its environs. Danzig had a predominantly German population, Poles constituted 1% of its inhabitants. After the German invasion of Poland in 1939, the Nazis abolished the Free City and incorporated the area into Reichsgau Danzig-Westpreussen. In the 1920s the Polish government developed the village of Gdynia, which was on the stretch of the Baltic coast accorded to Poland under the Treaty of Versailles, into a large city and port.a

- The Polish community was the largest minority in Danzig. Its activists stood up against the Germanisation and secularisation policies of the German government and sought to protect the rights of Poles living in the Free City.a

- Dora-Buchenwald (aka Dora-Mittelbau and Nordhausen-Dora) was a sub-camp of Buchenwald located near Nordhausen in Thuringia, Germany. It supplied slave labour (including evacuated survivors of camps located in occupied Poland), to extend the nearby tunnels in the Kohnstein and manufactureing V-2 rockets and V-1 flying bombs. In 1945, most of the surviving inmates were evacuated by the SS. On 11 April 1945, US troops freed the remaining prisoners.a

- Danzig City Grammar School.b

- Philomath Circles were secret Polish youth organisations which operated throughout the 19th century under Prussian rule in Pomerania, in towns like Chełm, Brodnica, and Chojnice. Most of their members were Polish grammar school students. The first to be set up was the Chojnice Mickiewicz Circle, which later changed its name to the Tomasz Zan Society. In 1937 it celebrated its centenary (see Teka Pomorska II, 1937, issue 11). The Pomeranian philomath circles looked back to the Philomath Society, the secret Polish student organisation operating from 1817 to 1823 at the Imperial University of Vilnius and co-founded by Tomasz Zan and Adam Mickiewicz.a

- Westerplatte is a peninsula located on the mouth of one of the Vistula channels in the Bay of Gdańsk. From 1926 to 1939 it was the location of a Polish Military Transit Depot, sanctioned within the territory of the Free City of Danzig. It was the site of the first German attack on Polish forces, starting the Second World War on 1 September 1939.a

- About 10 thousand prisoners passed through Neufahrwasser, Stutthof, and Grenzdorf camps from September 1939 to late March 1940. About 3 thousand were released.a

- Dr Mirau’s activities have been described in Siniecki’s article published in the 1975 edition of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Its English translation, “Episodes from the history of the Stutthof prisoners’ hospital,” is available on this website. Follow the link to read it.a

- The Schichau-Werke was a German engineering works and shipyard on the Vistula Lagoon. It also had a subsidiary shipyard in nearby Danzig.a

- Balys Sruoga (1896–1947) was a Lithuanian poet, playwright, critic, and literary theorist. Sruoga’s best known work is the novel Forest of the Gods, based on his own life experiences as a prisoner in Stutthof, where he was sent in March 1943 together with forty-seven other Lithuanian intellectuals after the Nazi Germans started a campaign against potential anti-Nazi agitation in occupied Lithuania.a

a—notes by Maria Kantor, the translator of the article; b—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

References

I have used the following materials:

- Zegarski, Witold. 1969. “Dr Witold Kopczyński.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 201–204 .

- Kłusak, Miron. 1971. Z problematyki medycyny w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych. Sytuacja więźniów chorych w Stutthofie 1939-1945. Gdańsk: Akademia Medyczna w Gdańsku, Studium Nauk Politycznych, 81–119.

- A. Pilarczyk’s oral relation, recorded by Bogdan Siniecki on 24 November 1972.

- Aleksander Witkowski’s letter of 23 October 1944, in the private collection of Bogdan Siniecki.

- Sruoga, Balys. 1965. Las Bogów. Gdynia: Wydawnictwo. Morskie, 229–255. Polish translation of the original Lithuanian book Dievu miskas: memuarai, Vilnius: Valstybine Grožines Literaturos Leidykla (1957). English translation: Forest of the Gods: Memoirs, Vilnius: Vaga (1996).

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland.