Author

Maria Jezierska (nom-de-guerre Elżbieta) was born on 2 February 1916 and died on 4 June 1994. Jezierska’s family moved in Warsaw in 1919, and in 1935 she graduated from high school and enrolled at the University of Warsaw to study Polish. Starting in autumn 1939, she engaged in anti-Nazi underground activities and as liaison in Union of Retaliation (Polish Związek Odwetu), a branch of the Union of Armed Struggle (Polish Związek Walki Zbrojnej). Arrested on 13 June 1942, she was first detained in the Pawiak prison. On 12 November 1942 she was transferred to KL Auschwitz (receiving prisoner No. 24449), and then, on 13 October 1944, to Ravensbrück (receiving prisoner No. 73038). Jezierska was liberated on 3 May 1943 in the Rostock area and returned to Poland on foot. After the war, she earned a degree in Polish from the Jagiellonian University in Kraków and worked for a number of academic publishers. She was an active member of former prisoners’ associations and worked as an archivist for the Main Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes in Poland. She retired in 1976, dedicating her time to work on academic publishing. In 1962, Jezierska and T. Hołuj published the results of their research in Kominy: Oświęcim 1940–1945, Warsaw: Czytelnik; 1962.

Sources: kpbc.ukw.edu.pl/ and auschwitz.org.

In the realities of Nazi German concentration camps, prisoners’ private bodily functions became a serious, insurmountable problem which often decided about their life and death. In normal conditions, those functions are usually dealt with in medical contexts, because, especially for those who do not represent the medical professions, they seem gross, embarrassing, and annoying.

Civilized people hardly ever speak of certain aspects of human physiology, such as urination, defecation, and flatulence, or toilets and sanitation, faeces and their disposal, and the sewerage system (except of course during training programmes for doctors and nurses, or caregiving to infants and the elderly). Presumably this is why the awkward and perplexing, but significant problem of excrement and its disposal in the concentration camps that operated between 1939 and 1945 (if I may briefly define it so) has not been studied and treated separately so far. I would insist the problem was really important: it contributed to the general torment of incarceration, it caused many deaths, and was responsible for the outbreak and spread of epidemics, thus producing long-term effects survivors are still burdened with today.

Those who ask me about the camps tend to think the main source of oppression was harassment and physical violence, sometimes they also add hard labour and starvation to that list. Yet, life in the jails and camps, especially when they were overcrowded, presented a range of inconveniences that may seem minor, but proved a really great nuisance. The disposal of bodily waste was one of them. One can find many corroborative remarks in the accounts and memories of the survivors; I shall quote some excerpts.

I will begin by offering a few commonplace observations which are indispensable for my argumentation and the proper assessment of the problem.

- Every living human must eat and drink, and likewise, on an everyday basis, excrete urine, faeces, and digestive gas. When forcibly prevented from doing so, he or she will suffer and may even fall ill.

- Depending on a particular individual’s mental and physical constitution, the bodily functions are performed at different times and with a different regularity, sometimes in an untypical or anomalous way. Additionally, some people may not be able, or feel they are not able to control their sphincter or are incontinent (they suffer from incontinentia urinae).

- Those who suffer from certain conditions of the stomach, intestines, and bladder need to use the toilet more often than healthy people, sometimes instantly.

- From our early years, we are trained not to expose our private parts and we grow to be embarrassed by our bodily functions. We would not perform them in front of others, especially people of the opposite gender. We even use euphemistic expressions to describe those functions and the special places reserved for them.

- We are perfectly aware that urine and excrement are filthy and may spread diseases, especially in infectious hospital wards. We find the filth of bodily excretions repugnant.

- We like to keep out toilets neat and clean, with one cubicle to one person. We also know that those people who cannot move around unaided need to be helped to get to the toilet.

The Germans took the opportunity to turn all those human habits against their prisoners. It is all the more astounding that they have always prided themselves on being a particularly civilized nation, also as regards sanitation. It should be noted that they tended to describe Polish people as “dirty,” using the phrase schmutzige Polacke, while sometimes the dirt was not the result of the Poles’ neglect of hygiene, but instead was due to the conditions in German jails and concentration camps. Perhaps surprisingly, the cleanly and cultured Germans decided to ignore the problem of water supply and sewage disposal in their concentration camps. But actually, the provisional arrangements were part of the system targeted to humiliate the prisoners and put them in a predicament that made it possible to treat them as subhuman, as inferior creatures, practically draught animals—and then to beat and kill them without scruple.

The situation was different in the Nazi German jails from the situation in their concentration camps, so let me start with the jails. Those located in existing, purpose-built penitentiary buildings had relatively well-kept flush toilets. Unfortunately, as the cells were overcrowded and the detainees were not allowed to use the toilets very frequently, the outcomes were rather unpleasant.

For instance, in the women’s section of the Pawiak jail in Warsaw, which was called Serbia, the cells were about five by six metres and had just one small window. Each cell was occupied by up to 42 women, who were allowed to use the “corner,” that is a toilet in the nook of the corridor, only twice a day, in the morning and in the evening, for fifteen minutes. The toilet had just five seats, so long queues formed in front of each of them. The women waiting in line rushed the occupier of the seat: they all wanted to use the toilet within the prescribed quarter-hour. Not allowed to defecate for long periods, the women were usually constipated, and often unable to urinate when told to do so. They were in such a hurry that many did not manage to evacuate the bladder and bowels in the normal way.

The cells were equipped with a “can,” that is a lidded metal bucket, but you could hardly use it in an overcrowded cell, as some of the prisoners had to sit and sleep next to it.

The prisoners were prone to pain from flatulence, and the condition was aggravated by the diet consisting of brown bread and cabbage or swede soup. Their distended bellies felt painful and made it hard to breathe.

Attempts were made to “tap your way out” to the “corner” during the day, that is to knock on the cell door to attract the Ukrainian1 guard’s attention and see if he was in a mood good enough to grant you the favour, which you could not ask too often: once a day at the most.

It was only at night, when the lights were out, that the “can” was in constant use by those who needed to pass urine, and you could hear a fusillade of gas expelled from the intestines of apparently sleeping prisoners. From evening until morning you could not pass stool. I remember that one inmate, a sophisticated lady, was caught in the act of using the can for that purpose: her equally sophisticated cellmates wanted to beat her up for the trespass. Brought to tears, she had to explain that she always used to defecate at night and now it was impossible for her to shift that habitual time.

Resisting the urge to urinate or defecate and, having to do it instantly when ordered, caused cramp, constipation, and bladder pain, and even more serious conditions such as post-hepatic jaundice, which I suffered from, too.

Prisoners held in isolation cells were in a slightly better situation, because they used the toilet alone, did not have to undress in front of other inmates or to hurry: their ten minutes did not have to be shared. It has to be added that the cistern over the toilet next to the window served as a “post-box:” prisoners from isolation cells could leave and pick up their illicit correspondence there. Also, in their cells they had a “can” to themselves, so if they decided to use it to defecate, they were the only ones to put up with the smell until they were allowed to go to the “corner” and empty the content.

A normal toilet, easily available and used by one person at a time, was available only in the prison hospital. It was one of the greatest luxuries in the place, fully appreciated by those women who were transferred from a cell to the hospital room (and probably unremarkable for those who have never been put to such inconvenience).

Other prisons, such as Fort VII in Poznań, had similar lavatories to the Pawiak ones.

The only toilets for prisoners on this floor of the building were situated in the corridor of the right wing. The inspectors observed that the facility, which was 5.5 by 4 metres, had five toilet seats, which a group of about thirty prisoners could use for about 4–5 minutes.

None of the cells had natural lighting, because they had no windows [and no fresh air, either—M.E. Jezierska]. The stale, foul-smelling air was all the worse for the buckets that were kept inside for defecation.

Olszewski 1971: 14, 44, 45

Gerard Knoff, who was imprisoned at Neugarten in Danzig (now Gdańsk) in 1939, described the conditions there:

One day, after lunch, Zachieja [a guard] opened the door and one of my cellmates went out to wash our bowls. During that time Zachieja was standing at the door and we had to wait, too. We wanted to use the spare minutes to go to the toilet on the opposite side of the corridor, so as not to spoil the air in the cell. Of course, it was up to Zachieja to grant us permission or not. On one occasion, I managed to obtain the favour. When I was in the toilet and the guard could not see me, another prisoner came in. It was Tomasz Tylewski, who seemed a bit embarrassed, because he recognized me. . . . Sitting side by side, we exchanged a few words . . . of consolation. Yes, it was an unusual encounter, the only one that I had with such an honourable man in such circumstances.

Knoff, Archiwum Muzeum Stutthof—hereafter referred to as AMSt.—ref. no. RT XVI, p. 199

Janusz Tempski described the quarantine in the Pawiak jail.

In the Pawiak, we were led into a filthy cell in the basement. We were all together in one room, which was damp, dirty, lice-ridden, and unbearably hot. . . . It was impossible to lie down to sleep, standing room only. The stench was unimaginable, because we were never let out of the cell, neither to wash nor to answer the call of nature. The can was overfull and urine dripped out onto the floor, which was soaking wet in any case.

Tempski, AMSt., RT III, p. 289

The situation was even worse in prisons housed in (mal)adapted buildings, which usually had outside lavatories or unroofed latrines, that is simply earth pits with a perch to squat over.

The sanitation systems in penal and concentration camps were just as inconvenient; there defecation was still an ordeal, though for slightly different reasons. In theory, the latrines were accessible, but in practice prisoners were not able to use them any and every time they needed to.

For instance, at Birkenau in 1942, the latrines were situated behind the blocks and it took time and effort to reach them. Practically all the prisoners had Durchfall (starvation diarrhoea), so sometimes they did not manage to reach the latrines soon enough. Their underwear and shirt would be soiled with stool (and clean ones cost at least two rations of bread on the camp’s black market), or, if the prisoner decided to defecate on the spot, near the blocks, and was caught by the Nachtwache (night guard), she was brutally beaten. Anyway, going to the toilet at night, considering that in the winter you had to put all your gear on, meant extra exertion and less time to rest, while we suffered from permanent sleep deficit.

In the morning, before the roll call, all the prisoners ran to the latrine, which was a cement pit with no seats, but only a narrow, slippery and filthy ledge. Of course, no one would dare to sit down: even when a sick woman was barely able to keep up on her feet, she had to defecate in this position. The stool, loose due to diarrhoea and flatulence, spurted out far and wide, soiling the women on the opposite side of the ditch. If a prisoner squatted on the cement ledge, she could (and often would) fall into the ditch, because other women would be elbowing their way to get through the crowd and use the latrine before the morning roll call: there was not enough room for all those who had to use the toilet at the same time. If a sick woman occupied her “seat” for too long, she would be grabbed by the head and pulled away. If a prisoner soiled the ledge, she would be beaten with a wooden club by the “toilet attendant” (at the time it was a German prostitute). All these things turned a prosaic procedure into a nightmare and a daily ordeal.

I can’t put it into words that will make it as foul as it was. No picture of the hell of Birkenau can match the horror that it really was.

Every morning, the blocks were surrounded by piles of excrement. As soon as the women from the first Warsaw transport arrived in the camp, they were ordered to clean it up. However, they received no tools or gloves, so they had to use their bare hands. Later it turned out that their section of the camp had no washroom, nor any taps, so they were unable to wash their hands and in the evening they had to hold their bread in their dirty hands. Even if we disregard the feeling of disgust and revulsion, there was still the question of bacteria—and the typhus raging in the camp.

Later on, in 1944, the situation in Birkenau changed. The latrine ditches were covered with cement slabs that had holes in them. There was still not enough room on them, but at least you could not fall in. The angry, rushing crowd still jostled to get one of the few seats, but having used the toilet, you could go to the washroom and at least rinse your hands. Those who have never experienced the predicament cannot even guess what a difference that made.

It has to be noted that during the roll call and while the working units were preparing for work or marching out to work, no prisoner was allowed to go to the toilet. Yet the latrine was actually a place where those who wanted to avoid a day’s work would hide; if discovered, they were beaten or even put on the penal report. Neither sickness nor pleading could help them. And the roll call could go on for hours and hours.

As there was no toilet paper, rags were used instead. This is why very often the drains would clog up. To prevent blockage, iron bars were installed over the holes. Nevertheless, the male sewage cleaners’ Kommando was always very busy. In the last period of Birkenau’s operations, waste ponds were built, but they were never started.

There were no “cans” or chamber pots in the blocks. In 1944 toilets started to be built inside the blocks, yet they were never used before 1945.

The hospital had different rules. At either end of the block there were lidless wooden containers with poles [so that they could be carried] or “cans,” that is buckets mounted in wooden frames, on which you could sit. These vessels were emptied into the latrine by the cleaners. It is hard to describe how much excrement landed on the dirt floor of the barrack or on the camp street in the process. And it was the faeces of sick inpatients. Obviously, neither the inside of the containers nor of the buckets was ever washed or disinfected.

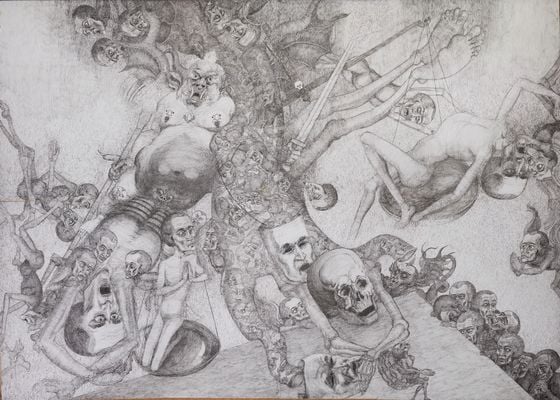

Last Judgment: Inferno. Inspired by Brunelleschi’s Dome of Florence Cathedral. Marian Kołodziej. Photo by Piotr Markowski. Click to enlarge.

In 1944 things changed. The outer casings of the buckets were painted and had to be washed, and the patients got chamber pots. That was of immense help to those who had diarrhoea (or, for that matter, typhus), because previously they often soiled the bunks, being unable to control their bowels for the time it took them to reach the end of the block.

Needless to say, the beds were still being soiled by those who were unconscious and could not control bowel movement. This applied especially to typhus patients. Another common, aggravating problem was nocturnal bedwetting (enuresis nocturna). Luckily, in 1944 the hospital was divided into wards, which prevented the spread of epidemics at least a little.

It has to be stressed that the changes for the better were not brought about by the SS hospital personnel, but by the prisoner doctors.

However disgusting, Birkenau was not an exception. Here is a description of a Stutthof latrine from the account of Jan Starzyński:

We [new arrivals on 21 June 1941] had to stand at attention, in rows of four, until dawn. There was only one break during the night, when we were allowed to use the toilet. At that time the camp had no toilets to speak of: we had just a perch to sit on in a makeshift latrine.

Starzyński, AMSt., RT IV, p. 217

This account is by Roch Kleszcz:

Many people with diarrhoea had to get up at night to obey the call of nature. You had to go out of the barrack and shout that you wanted to cr**. Sometimes the guard would shout back, sometimes he’d shoot. . . . With lots of people with the trots, you had to queue up for the jakes, where there were no seats vacant, so people defecated everywhere and the stink was overpowering. In the morning the excrement was cleaned up, usually by Catholic priests [which was one of the harassments], and we would sprinkle the floor with talcum powder [wash the floor with chlorine solution]. Our dormitory slept 150–200 people. Those were the conditions we had to live in from November 1939 to June 1940.

Kleszcz, AMSt., AMSt., RT XV, p. 57

Mieczysław Filipowicz voices the following view:

In 1939–40, the latrine was another problem. A prisoner who wanted to leave his barrack to go to the toilet had to stand at attention in front of the barrack, turn towards the guards’ tower and report, “Prisoner number such-and-such is going to the latrine.” Then, on the double, he had to run there, taking the shortest route. He had to report again when he returned. . . . The latrine supervisor was a deaf and dumb Pole. He was assigned this function by the camp authorities and was the only one to enjoy the privilege of not being beaten. His responsibility was to keep the latrine clean. Jewish prisoners scoured it at night, but it was still open for normal use while they were cleaning it.

Filipowicz, AMSt., RT IX, p. 40

Franciszek Wojtysko described another camp-specific complication:

Reaching the lavatory was a problem, we were not strong enough. We helped the weaker fellows get there; it took us up to an hour, though it was only 300 metres away.

Wojtysko, AMSt., RT XVI, p. 176

Wojtysko was talking about those who suffered from diarrhoea and were weak and emaciated. They were not taken in by the hospital and if they soiled the bunk, the barrack floor or the environs of the block, they would be severely punished. Sometimes they were simply beaten up on the spot by the block functionaries or, worse, the details were made known to the Blockführer (the block’s SS supervisor). He would then draft an official report. The prisoner being punished would be leant over a whipping stool and received 10–25 blows delivered with a wooden club, which was recorded in his punishment card (some of these records have been preserved). Actually, prisoners either received more blows or did not get any food for a few days, or were forced to work or exercise strenuously on a Sunday.2

Out of respect for the victims of such abuse, I shall not disclose their names; instead, I shall give the reference numbers of the archival documents with the “sentences” approved by the WVHA (Wirtschaftsverwaltungshauptamt, the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office) in Berlin.3 The punishment was meted out in the presence of all the prisoners to teach them a lesson and prevent further “offences.” The doctor who certified the “culprit” was able to stand the punishment was completely unconcerned about the prisoner’s health or the reasons why he had soiled his bed. Consequently, some of those who were sentenced to such severe punishments died soon after they had been “disciplined.”4

Another problem was keeping the latrines clean: scouring the seats and floor in what could pass as communal toilets, or emptying makeshift latrine pits with no sewage system. The excerpt below comes from Alojzy Ruciński’s account, describing the facilities in an adapted prison (as I have said before, purpose-built penitentiary buildings had regular water and sewage installations).

[In 1939 in Gdynia, a large number of Poles were herded up and detained in the Morskie Oko cinema], where we spent the whole night, the following day, and yet another night. It was the first occasion when I could observe the appalling conduct of the SS men. There was only one small toilet to that huge crowd, so no wonder it was overfull in no time. The SS men picked a man in gold-rimmed glasses who looked like an intellectual and forced him to empty the toilet with his bare hands.

Ruciński, AMSt., RT IX, p. 239

In the early phase of the operations of Stutthof concentration camp, cleaning the latrines was one of the harassments that Catholic clergymen and Jewish prisoners were subjected to. Father Alfons Muzalewski writes:

Stutthof camp reserved one kind of job exclusively for priests. It was cleaning the latrines. Father Wiecki and Father Komorowski were two of the cleaners. They were harassed while doing the job.

Muzalewski, AMSt., RT IX, p. 150

Zbigniew Nielepiec describes the ordeal in the following way:

The dirtiest job went to the priests and the Jews. Their unit was called the Scheisskolonne. They had to empty the latrine pits by getting down into them and filling up buckets which were then discharged into a tanker. There was nowhere they could wash when the shift was over.

Nielepiec, AMSt., RT VI, p. 83

In the early period of Stutthof’s operations, there were not enough priests and Jews to do the job, so another group that was given the humiliating assignment were members of the educated class. Dr Julian Węgrzynowicz, a physician, writes:

The commandant of the Mielenz sub-camp, every inch a sadist, found special pleasure in harassing members of the intelligentsia. On his orders, I had to clean all the toilets. He found it hilarious and, laughing, commented: “Hey, doc, you gave this loo a really good scrub!”

Węgrzynowicz, AMSt., RT VI, p. 231

Survivor Leon Adamski gives a description of latrine cleaning in Stutthof:

In July or August 1941, a few inmates and I were assigned the task of emptying a deep latrine pit. We had to lower a long ladder into it. The man standing down there had to fill a bucket and pass it to another fellow standing above and so on, until the content was discharged into a barrel. When it was full, we had to pull it into the woods, outside the camp perimeter. Grave-like ditches, two metres long and about one metre wide, had been dug there. We poured the excrement in, covered it up with branches to hide the contents, and moved on to the next ditch. . . . The ditches were fairly deep. . . . A few weeks later all the blueberry bushes in that clearing went yellow and dry, presumably the soil had got contaminated.

Adamski, AMSt., ref. no. a I 1

The SS men flaunted their arrogance and cruelty during the callous “games” which they liked to play and which now may seem hardly believable. Here are some examples.

The women who were incarcerated in Fort VII in Poznań say they were “forced to remove excrement [from the toilets], which was then poured all over them.

Olszewski, 54

There were also instances of forcible coprophagia in Fort VII:

The Gestapo . . . kept tormenting a certain shopkeeper. They beat him up, made him crawl, and jumped on him. . . . He defecated. They ordered him to eat his faeces and continued molesting him until he obeyed, to their savage joy. There was a lidless bucket used as a toilet in the cell. The smell was unbearable. . . . The bucket was always so full that you couldn’t carry it out without spilling some of the content. Whatever dripped onto the floor had to be licked clean by the prisoners.

Olszewski, 54–55

Dr Lech Duszyński describes the “wit” and “ingenuity” Stutthof’s SS men manifested during one incident:

Near the camp there was a sluggish channel into which the sewage was dumped. One day one of the SS men had an idea—a brainwave by Nazi standards—that the sewage ditch could be used to transport timber. So the logs were not carried on dry land any more, but pushed downstream by prisoners standing up to their chest in the sewage. Now, in our climate, you do not dive into the river in October, even in the best of weathers; neither do you work standing in cold water all day long. Yet the playful SS men came up with one more diversion. One of them, holding a sturdy club, would stand on a footbridge over the canal. As the prisoners pushed the logs along, they had to duck their heads into the foul water to pass the bridge. Whenever a head bobbed up to the surface on the other side, the SS prankster clubbed it. Depending on the force of the blow and the prisoner’s resilience, the victim would lose consciousness for a time and often took a gulp of the gunge. Indeed, that was the best part of the game: the prisoners eating their own excrement. Those put to such abuse fell ill because of the cold . . . or contracted diseases of the digestive tract . . . .

At night, the ailing men were not allowed to use the toilet very often. It stood in the middle of the camp and the guard keeping watch from his tower did not like to see the prisoners outdoors. He yelled: ‘You son of a bitch, what’yah doing there so often? Planning an escape? If I see you again, you’ll get a helping of my coffee beans, and you won’t want to c*** again!’ Terrified prisoners would defecate on the bunks. The straw bedding on the floor became rotten, turning into a hotbed of dangerous stomach bacteria.

Duszyński, AMSt., RT XI, p. 30 ff

Still, a “quick-witted” SS man was better than a furious one. Dr Lech Duszyński, whom I have quoted before, remembered one such incident:

An inebriated SS commander of the sentries, an NCO called Dirks, got the urge to kill a prisoner with severe TB. . . . When his drunken search for the sick man proved unsuccessful, Dirks insisted it must have been Dr Kopczyński who had helped him hide away in the toilet. The situation was getting out of hand when the frenzied Dirks found that the poor wretch was actually there. Kopczyński grew so panicky that he was unable to say anything in his own defence. A major disaster was averted by Palasch, an SS man from Danzig, who was the supervisor of the unit and just happened to come by. . . .. Incensed by the interference, Dirks kicked the toilet door open and, in full view of Dr Kopczyński, shot his patient several times, killing the man on the spot. Luckily, there was only one victim.

Duszyński, AMSt., RT XI, p. 37 ff

It has to be noted that in those camps where the toilets and washrooms were located in the barracks, they served as night-time morgues, too. At night, prisoners were not allowed to venture out of doors, and corpses had to be kept inside to be counted during the morning roll call. There was no separate room to keep bodies, and no respect for the dead. The corpses were treated as disposable waste.

The toilet or washroom was also the place where prisoners committed suicide and where their bodies were found. They took their lives either for reasons of their own or if forced by sadistic functionaries. Some of the victims were people with diarrhoea, who were got rid of in this way: they did not soil the floor or bed any more.

Outdoor latrines also served as hiding places for those who wanted to escape. The would-be fugitive had to wait out the time when the camp or the workplace was being searched by the SS men and their dogs. He stowed away in the pit in the hope that he would be hard to discern in the mass of faeces or scented by the dogs in the foul-smelling air. Such stories are hard to believe, and indeed it must have taken a really desperate man to make such an attempt. Yet, incarceration in the camp was such hell that some detainees really came up with ideas of this kind. Here is an account by Henryk Tempczyk:

One of the prisoners from the Warsaw transport escaped while working for the Epp company. The search was ineffective, but after two days we saw him standing in front of the camp shop, awaiting the ordeal that every fugitive who was caught had to suffer. It turned out that he had hidden away in the latrine pit before his shift was over, up to his neck in faeces until dark. . . . In the evening, he clambered out of the pit, took off his reeking gear, washed himself in the ditch and managed to sneak into the workshop, where he changed into dungarees and spent the rest of the night. At dawn, he set out on his journey and walked along the Gulf of Danzig towards Kahlberg (now Krynica Morska), having no idea where he was heading . . . . After a long while, he came to a road and struck up a conversation with a German passer-by who promised to show him the right direction, but . . . turned him in at a police station.

Tempczyk, AMSt., RT I, p. 332

Ambroży Łepek described another similar escape:

One evening, after work, our unit was kept longer. Two prisoners were missing. The yard was searched with the dogs, and the SS men checked all the nooks and tanks. . . . We had to stand waiting for three hours. Then the SS men went with the dogs to the latrine to examine the pit. They found the two escapees there, with just their mouths and noses over the surface, covered with some paper. They were told to get out and the dogs were sicced on them. Later the limp, butchered bodies were dumped on a cart and transported to the camp.

Łepek, AMSt., RT XXI, p. 127

There is a similar incident in the Sachsenhausen recollections of Wawrzyniec Węclewicz:

On one occasion a fugitive was discovered in a cesspool near the latrine. I suppose he had been working in the unit emptying those pits, so he knew how they were built. Having checked the securities, he decided to wait out the search inside the cesspool. At one point the pit was surrounded by the searchers, and he had to duck under the surface. He put his head out only when the depth was being probed with a pole. He was still alive when they dragged him out, but did not survive the flogging.

Węclewicz 1983: 167

The lamentable effects of punishment by flogging are described by Józef Szarkowski:

The other night, two fellow prisoners escaped from the Pröbbernau sub-camp. They were pursued, but not caught. . . . Görke, the commandant, had warned us on many occasions that ten of us could be shot for each escapee. . . . In the evening, the punishment was meted out to the kapo who supervised their working unit of twenty men as well as to those prisoners who had been sleeping next to them. . . . The prisoners had to line up in a rectangle around a whipping stool. Two SS floggers took off their jackets and, holding the whips, positioned themselves on either side of the stool. The first man to be flogged was the kapo. We were told to remove our headgear and count the lashes. The “culprits” had to lower their trousers and received the blows on their bare buttocks. Two SS men were holding the victim’s legs and two more held his arms. At first the prisoners who were being flogged pressed their lips together and kept their silence. But the whips quickly cut into the skin and blood was spurting out, so eventually we could hear them shrieking and groaning pitifully. Soon a mix of blood and excrement was squirting out and up into the air. . . . The groans got softer and softer, until finally the flogged prisoner lost consciousness. His backside turned into a great big, raw wound which took a month to heal. We had to watch the show while the SS men had their fingers on the triggers, pointing their guns at us. . . . The punishment was usually 30 lashes, sometimes 50, or even 100.

Szarkowski, AMSt., RT XIV, p. 260

Those who needed the toilet were in trouble particularly during the march (or, less frequently, the ride) to work and back to the camp. Detainees were not allowed to break rank, and the journey could last an hour or two. Those with even a mild kind of diarrhoea were at a grave disadvantage: they had no change of clothes and nowhere to wash the dirty garments. The consequences could be dire. I decided to withhold the name of the author of the following account:

We were sent to the village to dig a garden. . . . I happened to have one German mark on me. I saw that [our host] the baker took the rolls outside to cool off. So I wanted to use the mark to get some bread. I put it on a post and went away, but he understood my intentions, took the money, brought back some breadstuff and left. My mark bought me 13 rolls and 4 pounds of bread (a roll was 3 pfennigs and a loaf of bread was 15 pfennigs). I wanted to take them back to the barrack, because we were reasonably fed by the host, but then in the camp we went hungry and were starving all the time. So I could not wait until the evening and gobbled up everything at one go, the rolls and the two kilos of bread, and the supper that we were offered. I have no idea how I managed to fit it all in.

But on our journey back we were late and the guards kept hurrying us up to get to the camp in time for the 6 o’clock roll call. On the way, I felt I needed the toilet. It was useless to ask permission to nip into a wayside ditch, as no one was allowed to stop the entire column—so I soiled my underwear and trousers. We scooted to the roll call square. . . . I lasted out the assembly, somehow or other, but then hurried to the toilet that had just been put up by the hospital. There I managed to clean myself up a little and chucked my underpants, made of thin, dark blue fabric, into the toilet so as not to be found out. So far so good. But now, how to get another pair? . . .

I had to procure a pair, because when we undressed for the night, we had to fold all our gear up in a neat pile, which was checked. If any item was missing, the prisoner was in for trouble. I went to talk to Czesiek Kmicik in Entläusung [the delousing room]. . . . Unfortunately, Czesiek had just dispatched all the laundry to be washed and could not spare a single pair. So how could I wangle what I needed? Next to where I lived was the German prisoners’ dorm room, number seven, and at the time I was in the block next to the fence. . . . The middle room, where we took off our clothes, was connected to the Germans’ room. I made sure to stand next to the last stool in the row, because then the man undressing by my side was a German. Well, perhaps I wronged a fellow prisoner, but he was German, so he stood a much better chance of being let off. So I pinched his underpants, put them in my pile of clothes, relaxed and went to bed.

AMSt., RT IV, pp. 225–6

To complete the picture, I should add that the toilet served many other purposes, besides the obvious one. For instance in Birkenau, women prisoners would hide there after the assembly of the working units, so as to avoid a day’s toil in the fields. The functionaries and SS women used to run a hue and cry for them, but the building continued to be used as a hideout: it had two doors at the opposite ends, so prisoners hoped they would be able to run away if chased. Skiving off from an outdoor job on a frosty or rainy day was a big temptation.

One of the peculiarities of Birkenau was that the women’s sector had a men’s toilet. The men’s Kommandos of bricklayers, sewage cleaners, roofers etc. who entered the sector to work there until the evening roll call were able to use a small toilet, the last one in a row, located in a building that was a lavatory-cum-washroom. During the night it was used by the women.

A discussion of the prisoners’ need to excrete should also consider the conditions in which they travelled from jail to concentration camp, between camps, or when they were evacuated at the end of the war. With the front line getting closer and closer, sometimes all the prisoners in a camp were forced to board cargo trains or join death marches.

Occasionally, the prisoners travelled from jail in a prison car, which had a toilet, but that was a rare situation. Large transports were dispatched from one camp to another by train in primitive cargo cars, locked and bolted. Dozens of prisoners were squeezed inside and often had to spend four days there before they reached their destination. We can only imagine what went on inside: the SS men feared their wards would try to escape, so they never let them out for a break.

During the evacuation marches, the prisoners could defecate in roadside ditches, in a hurry, in the presence of all their mates, and had to make sure they did not lag behind at the end of the column: the SS men shot anybody who was unable to keep up with the rest. Prisoners were locked up in barns, cowsheds, or other buildings for the night, and not allowed to leave them.

Bernard Mizerski remembers the following incident:

[During the evacuation march] we reached Buckowin [now Bukowina]. We had to spend the night in the church. It was packed tight. The main entrance was guarded and no one was allowed to get out, not even for the toilet. The church was completely fouled up in the course of the night.

Mizerski, AMSt., RT XVII, p. 117

In every concentration camp, the penal unit was a particularly harassed group. Those prisoners lived separately, in specially fenced off buildings, and suffered even more persecution. This is what Wawrzyniec Węclewicz, whom I have already quoted, wrote about the penal unit in Sachsenhausen. We should bear in mind that he was deported there before 1939, which means that his fellow prisoners were native Germans. But even for them there was no lenient treatment.

Moving your bowels was yet another torture. The latrine could not have served all the prisoners in the barrack even if they had been well, what with the majority suffering from diarrhoea and urinary tract disorders. We tried to conceal our ailments, because we prisoners of the penal unit had to comply with stricter regulations in every aspect of our camp existence, including medical aid. We were fully aware that any request for treatment could bring the worst possible results. If somebody’s strength failed, so that he was unable to hide his problem any longer . . . or to elbow his way to the latrine in time, he could not expect to live longer than a few hours. . . . The sanitary conditions in the main camp were almost identical to those in the penal unit; it was just one more element of the system to make people crack up, physically and mentally.

Węclewicz, 126, 128

I included the last sentence in order to proceed to my conclusions. My purpose in describing the obnoxious aspects of incarceration in a concentration camp was not simply to bring them out into the open; I wanted to identify yet one more method of harassing and humiliating prisoners, of reducing them to emaciated wretches and finally annihilating them. Undoubtedly, the plan and the methods were premeditated, approved by the highest authorities, and let the functionaries in the jails and camps inflict extreme cruelty and release their basest instincts. Things that are natural bodily functions were turned into a shameful act, a cause of suffering and molestation. Things that were a symptom of a disease (such as typhus, dysentery or starvation diarrhoea) were viewed as a punishable offence. Sick prisoners were beaten or punished in other ways, and often did not survive the punishment, while the SS doctors never recorded any reservations about flogging on prisoners’ punishment cards.

To sum up, I have described indirect extermination methods and a system intended to strip prisoners of their dignity in order to destroy their souls as well as their bodies.

The humiliations were a real burden on the prisoners, as we can observe in an excerpt from the Stutthof recollections of Wiktor Ostrowski:

On 8 March 1945, when the Germans ordered another evacuation (from the sub-camp where some Stutthof prisoners had been transferred), I realized I would be unable to cover even two kilometres. . . . I went to the small barrack and dropped down on the straw bedding. The man lying next to me was Wroncki, who was running a fever. . . . In the evening I left the barrack and discovered that except for our room, the camp was empty. There were no Germans . . . In the small hours I had to go to the latrine. I covered the distance of 100 metres, but was so weak that on the way I had to sit down twice. Yet I did not enter the communal toilet, which was filthy and smelly. By the wall of that lavatory there stood a few separate cubicles, one of them with a notice Nur für Lagerführer, (only for the commandant of the sub-camp). I threw the door wide open and sat down on the commandant’s throne. . . . Please do not say it was ridiculous: for the first time I felt I was really getting my freedom back.

Ostrowski, AMSt., RT V, p. 138

Of course, it would be preposterous to say that this article is an all-embracing discussion of the problem, or even that it has attained academic standards. Yet, I consider it a worthwhile effort at least to acquaint the reader with this awful predicament of prisoners in Nazi German confinement, referring to their own accounts of this aspect of life in the jails and concentration camps.

***

Translated from original article: Jezierska, M.E., “Z fizjologicznych problemów bytowania w obozie.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1986.

- Many of the guards and wardens working in the Nazi German prisons in occupied Poland were ethnic Ukrainians, members of the minority that lived in pre-war Poland.a

- In Nazi German concentration camps Sunday was a day of rest—the only day in the week when prisoners could get a rest.a

- For punishment for soiling the bed, room, or clothes, see AMSt., ref. nos. I III 40330, I III 40 389, I III 40653, I III 42534, I III 42858, I III 43070, I III 43829, I III 26891, I III 40425. For punishment for spending too much time in the toilet, see I III 43719; AMSt. microfilms M 299, frames 109, 113, 90/2, 3, 90/6, 90/5.b

- For prisoners who died after the punishment, see AMSt. microfilms M 299, frames 116/2, 90/4, 116/1 (a prisoner with a chronic bladder condition), 58 (died one day after the punishment; 90/5 and 104 (died in detention).b

a—notes by the translator, Marta Kapera, PhD; b—notes translated from the original.

References

- Archiwum Muzeum Stutthof (Archives of Stutthof Museum). Reference numbers for specific documentation quoted in the article is given in the main body of the text.

- Olszewski, M. Fort VII w Poznaniu. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie; 1971.

- Węclewicz, W. Tyle śmierci ile dni. Poznań: Wydawnictwa Poznańskie; 1983.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland.