Author

Andrzej Jakubik, MD, PhD, born 1938, psychiatrist and psychologist, Professor at the Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology, Warsaw.

In the literature devoted to research on the permanent and long‑:term psycho‑physical consequences of internment in Nazi concentration camps, the predominant publications are psychiatric and psychological papers concerning post‑concentration camp asthenia, that is, the so-called KZ-Syndrome (Dąbrowski et al, 1965; Eitinger, 1961, 1964, 1970; Eitinger and Askewold, 1968; Gątarski et al., 1969; Herman and Thygesen, 1954; Jakubik, 1986a; Kristal, 1968; Leśniak, 1964,1965; Leśniak et. al., 1961; Matussek, 1971, 1975; Nathan et al., 1963; Orwid, 1962, 1964; Półtawska et al. 1966; Sarnecki, 1966; Sobczyk et al., 1980; Sternalski, 1978; Szymusik, 1964, 1974; Targowla, 1955; Thygesen, 1980; Waitz, 1961). Attempts to conduct synthetic analyses of the present research findings have also been undertaken (c.f. Kępiński, 1970; Matussek, 1971, 1975; Ryn, 1981; Thygesen, 1980).

The first papers concerning the consequences of internment in concentration camps appeared in the Scandinavian countries. In the year 1952, a group of Danish authors published a report on the somatic and psychological condition of former concentration camp prisoners; they showed that about 75% of the former prisoners had neurotic disturbances that were neurasthenic in character. They referred to these, in their opinion unspecified symptoms, as “repatriation neurosis” (c.f. Eitinger, 1961). Two years later, on the basis of detailed studies that had been carried out among former prisoners in Copenhagen since 1947, Hermann and Thygesen (1954) described the “concentration camp syndrome” (Konzentrationslagersyndrom). By this general term, they understood a wide spectrum of both somatic and psychological disturbances, caused by or associated with internment in Nazi concentration camps. Some authors refer to this collection of symptoms as “progressive asthenia” (Targowla, 1955) or “post-concentration camp asthenia” (Szymusik, 1964).

Numerous further studies show that in the clinical picture of KZ‑Syndrome, symptoms testifying to the organic damage of the central nervous system predominate, on the basis of which various psychopathological syndromes develop, mainly neurasthenic‑depressive and neurotic disturbances as well as encephalopathic ones. Many researchers showed that the inherent components of KZ-Syndrome are largely permanent personality changes (c.f. Jakubik, 1981, 1986a, 1986b; Leśniak, 1964, 1965; Półtawska et al., 1966). In both Polish and foreign sources, there is a predominant opinion that post‑concentration camp psychopathological syndromes and personality changes have a chronic character and in most cases they progress over the years, which does not create a prospect for successful recovery. Hence, the majority of authors are justifiably pessimistic about the chances for successful treatment.

Davidson (1970) is of the opinion that post‑concentration camp asthenia is “incurable” and the only assistance that can be offered to former prisoners consists of supportive psychotherapy and pharmacological symptomatic treatment, particularly for anxiety and depression. The therapy of patients “with a sense of their own insecurity and lack of trust in others,” should, above all, develop an emotional bond with the therapist who must clearly show empathy and acceptance of the patient as well as a readiness to help and “give hope for the future.”

A female prisoner after camp liberation

Winnik (1969) states that post‑concentration camp personality changes such as an inability to adjust, the weakening of defence mechanisms, the restructuring of the ego, the lowering of the efficiency of social functioning, character changes, and the gradual “degradation of personality” are either totally irreversible or else very difficult to treat. An even more pessimistic attitude is expressed by Dreifuss (1980) who refers to former prisoners of Nazi concentration camps as “permanent psychological invalids.” Based on an attempt to conduct psychoanalytical therapy of patients with the “traumatic anxiety syndrome,” Trautman (cit. Winnik, 1967) concluded that an analysis of the emotional life of former prisoners is difficult due to patients’ psychological resistance, which makes them oppose all attempts to reach out to their consciousness. Thus, in his treatment, Trautman used only the reactive method, focusing exclusively on the problems of “here and now.” A different view is presented by Brull (1969) who represents an existentialist‑humanistic approach to analytical psychotherapy. He is of the opinion that it is not difficult for the patient to reveal his traumatic experiences – in the sense of understanding and explaining the motives which had been pushed to the subconscious – whereas what is most difficult for him is to try and adjust to post‑concentration camp life, to “be in the new world.” According to Winnik (1967), a serious obstacle in the psychotherapy of former concentration camp prisoners is the fact that they instigate the defence mechanisms of isolation, denial, and distortion. For this reason, classical psychotherapy cannot be an effective method of treatment of KZ-Syndrome, and patients should be subjected to other types of psychotherapy. Winnik’s opinion is undermined by Erdreich (1984), who believes in the effectiveness of analytical psychotherapy in post‑concentration camp asthenia, on condition that psychoanalysis is used simultaneously in a “balanced” way, as a supportive and insight‑offering therapy; the fundamental aim of the latter is to reinforce the power of the patient’s ego. This type of psychoanalytical technique was described in detail by Erdreich and Zadik (1981). A similar view is represented by Ammon (1984) who is of the opinion that although post‑concentration camp personality changes – particularly with regard to one’s sense of identity, self‑assessment, the structure of one’s ego, or creative abilities – make effective use of individual psychoanalysis virtually impossible, the various forms of psychoanalytical group therapy are (or at least should be) effective.

Except for the sphere of sheer “casuistry,” neither the pessimistic nor the optimistic views of certain authors have yet been empirically verified. It appears that the a priori view of the incurability of post‑concentration camp asthenia, commonly accepted among experts, was not and is not conducive to undertaking any form of therapeutic activity, whereas the moderate optimism announced by a handful of researchers has not been proved by them, as mentioned above. In recent years, an additional factor that has discouraged specialists from undertaking any efforts to treat KZ-Syndrome, particularly by means of psychotherapeutic techniques, has been the advanced age of the former prisoners, accompanied by the process of premature aging.

Material and methods

In the years 1979-1981, attempts to treat former prisoners of various Nazi concentration camps by means of psychotherapy as well as psycho‑pharmacological methods were undertaken in a group of former prisoners who were diagnosed with post-concentration camp asthenia (KZ‑Syndrome) within the invalid certification scheme. At the same time, by means of carefully selected research tools, the effectiveness of the applied methods of therapy was assessed. Altogether 30 patients (17 women and 13 men), aged 55‑65, were subjected to treatment and research, and the patients were divided into three groups consisting of 10 people:

Group P: Subjected to individual psychotherapy,

Group L: Treated by pharmacological means,

Group PL: Subjected to individual psychotherapy and, at the same time, treated by pharmacological means.

The individual psychotherapy (consisting of 8‑10 sessions lasting 1‑2 hours) was directed primarily at symptomatic improvement, the strengthening of the sense of identity, raising the level of self‑acceptance, and increasing the sense of internal control. Yet, for the most part, it had the character of supportive psychotherapy. The patients belonging to groups L and PL received chloroprotixen (daily dose 30‑150 mg), a derivative of tioxanten with chiefly anxiolitical and thymoleptic properties. In all three groups, the period of treatment lasted an average of 3 months.

The following research instruments were used to measure the significance of the variables:

1. The Chicago Q-sort technique (c.f. Jakubik, 1981), which measures the level of self‑acceptance (that is, the degree of discrepancy between the “real self” and the “ideal self”) as well as its possible changes following psychotherapy (c.f. Butler and Haigh, 1954).

2. Questionnaire Delta of R. Ł. Drwal (1980), which measures the sense of internal and external control in the LOC (“Locus of Control”) scale.

3. The Ego-Strength Scale (Ego-SS) of F. Barron, which measures the strength of the ego; the latter is a self‑identity co‑efficient (the higher the strength of the ego, the stronger the sense of identity; c.f. Barron, 1969).

4. Concentration Camp Syndrome Scale (CCSS) – a questionnaire based on clinical lists of symptoms, which measures the degree of intensity of KZ‑Syndrome (the questionnaire consists of 70 sentence‑statements which are assessed by the subjects on a 0‑4 point scale).

Results

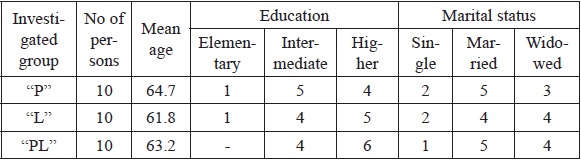

Table I illustrates the general character of the researched groups (P, L, PL) with respect to the demographic variables.

Table I: General data

Having assumed the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic, pharmacological, and combined treatment (psychotherapy + medication), the following research hypotheses were put forward:

H1: the treatment of post‑concentration camp asthenia leads

to a decrease in the intensity of traumatic symptoms.

H2: the treatment of post‑concentration camp asthenia leads

to an increase in the level of self‑acceptance.

H3: the treatment of post‑concentration camp asthenia leads

to an increased sense of internal control.

H4: the treatment of post‑concentration camp asthenia leads

to an increased sense of self‑identity.

In order to verify statistically the above‑mentioned research hypotheses, an operationalisation of the above‑mentioned data was first carried out, and subsequently suitable zero hypotheses were assumed (H01, H02, H03, H04), concerning a lack of influence of treatment on selected variables under investigation.

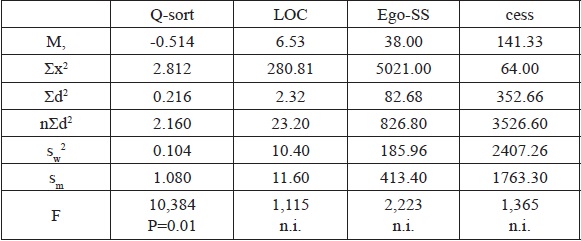

The results obtained in individual scales before treatment did not differentiate the groups under investigation in any statistically significant way. Due to the small number of persons subjected to investigation, the differences between men and women were not assessed. The results obtained immediately after treatment in groups P, L, and PL are illustrated by Table II.

Table II: Results

M, = inter-group mean value

∑x2 = sum of deviation squares

∑d2 = sum of squared differences between mean values within groups and the inter‑group mean value

n = number of measurements in a group

sw2 = intra-group variation

sm2 = inter-group variation

F = Snedecor’s test

Despite achieving considerably better results (as regards all analysed variables) within each group, when compared to the period before treatment, a significant statistical difference between groups occurred only with regard to the level of self‑acceptance. The variation analysis (see Table II) shows the incidence of inter‑group differences caused by a significant increase in the degree of convergence between the “real self” and the “ideal self” (F=10.384, p=0.01). The results obtained in groups P and L do not differ (chi sq.=3.906, p=0.05). Important statistical differences can be observed exclusively between groups PL and P (chi sq.=3.906, p=0.05) and PL and L (chi sq.=4.011, p=0.05) that partly confirms the second research hypothesis (H02), assuming an increase in the level of self‑acceptance as an effect of the treatment.

Yet an increase in the level of self‑acceptance occurred exclusively in the PL group, whose members were subjected to the combined treatment of individual psychotherapy with pharmacological treatment.

The results obtained in the remaining tests (LOC, Ego-SS, CCSS) in all three groups entitle the rejection of the research hypotheses, and the acceptance of suitable zero hypotheses concerning a lack of favourable influence of the treatment of post‑concentration camp asthenia, on such variables as the degree of intensity of KZ‑Syndrome, the sense of control, and the sense of self‑identity. Yet, despite the lack of statistically significant effects, in the PL group a slight positive effect of treatment was observed on the variables under investigation, which found its expression in a slightly decreased level of intensity of the symptoms (before treatment, Ms amounted to 153.2, whilst after treatment to 126.6); the shifting of the sense of control from an external to a more internal one (Ms values amounted successively to 7.86 and 6.22); and the strengthening of the sense of identity (Ms-45.00 and 36.00). As regards the clinical picture of KZ‑Syndrome, a tendency towards improvement was observed within such psychopathological phenomena as fear, psychological tension, depression, emotional imbalance, and headaches.

The results of the research on the effectiveness of treatment of post‑concentration camp asthenia confirm the findings of those authors who emphasise the relatively small effectiveness of therapy in the case of KZ‑Syndrome. On the other hand, they rule out total therapeutic nihilism, as they show a positive impact of psychotherapeutic activity (supportive psychotherapy) as well as pharmacological treatment. This type of combined treatment appears to be the best solution, although long‑term group therapy would likely be more effective. A confirmation of the latter hypothesis should be looked for in further empirical studies involving a more numerous group of former prisoners of Nazi concentration camps than that used for this study.

From Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1988.

References

1. Ammon G. The Dynamics of the Holocaust. Dyn. Psychiat.. 1984; 17: 404-415.2. Barron R. An Ego-Strength Scale which Predicts Response to Psychotherapy. J. Consult. Psychol. 1953; 17: 327-333.

3. Brull R. Trauma: Theoretical Considerations. Isr. Ann. Psychiat. Relat. Discip. 1969; 7: 96-108.

4. Butler J.M., Haigh G.V. Changes in the Relationship between Self‑concepts and Ideal-Concepts and Consequent upon Client-Centred Counselling. In C.R. Rogers and R.R Dymond (ed.), Psychotherapy and Personality Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1954.

5. Davidson S. The Treatment of Holocaust Survivors. In S. Davidson (ed.), Areas of Therapeutic Activity. Haifa: Kupar Holim; 1970.

6. Dąbrowski S., Schrammowa H., Żakowska-Dąbrowska T. Zmiany psychiczne powstałe w wyniku pobytu w obozach koncentracyjnych i eksperymentów pseudolekarskich [Psychological changes resulting from imprisonment in concentration camps and pseudo‑medical experiments]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1965; 21: 31-34.

7. Dreifus G. Psychotherapy of Nazi Victims. Psychother. Psychosom.. 1980; 34: 40-44.

8. Drwal R.L. Delta Questionnaire for Measuring Locus of Control. Pol. Psychol. Bull.. 1980; 11: 269-282.

9. Eitinger L. Concentration camp survivors in Norway and Israel. London: Allen and Unwin; 1964.

10. Eitinger L. Pathology of Concentration Camp Syndrome. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 1961; 5: 371-379.

11. Eitinger L. Syndrom koncentraćnich taborii. Cesk. Psychiat. 1970; 66: 257-266.

12. Eitinger L., Askewold T. Psychiatric Aspects. In A. Strom (ed.), Norwegian Concentration Camp Survivors. New York: Humanities Press; 1968.

13. Erdreich M. A Traumata-Oriented Psychotherapy. Dyn. Psychiat. 1984; 17: 419-431.

14. Erdreich M., Zadik Y. Psychotherapy of a Severely Traumatized Patient: The Struggle for Identity and a New Lifestyle through Work on Unconscious Traumatic Memories. Paper presented at the 13th International Symposium of the Deutsche Akademie für Psychoanalyse (DAP). Munich; 1981.

15. Gątarski J., Orwid M., and Dominik M. Wyniki badania psychiatrycznego i elektroencefalograficznego 130 byłych więźniów Oświęcimia-Brzezinki. Translated as The Results of Psychiatric and Electroencephalographic Examinations of 130 Former Prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp. Przegląd Lekarski. 1969; 25: 25-28.

16. Hermann K., Thygesen P. KZ-syndromat. Copenhagen; 1954.

17. Jakubik A. Badania empiryczne nad obrazem własnej osoby u byłych więźniów hitlerowskich obozów koncentracyjnych [Empirical studies on one’s self‑image among former prisoners of Nazi concentration camps]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1986; 43: 20-28.

18. Jakubik A. Obraz własnej osoby a pobyt w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych [One’s self-image and imprisonment in Nazi concentration camps]. In Wojna i okupacja a medycyna [War, occupation, and medicine]. Kraków: Medical Academy; 1986.

19. Jakubik A. Obraz własnej osoby a pobyt w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych. Problemy teoretyczno-metodologiczne [One’s self‑image and imprisonment in Nazi concentration camps: Theoretical and methodological problems]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1981; 38: 15-26.

20. Kępiński A. Tzw. „KZ-syndrom”. Próba syntezy. Translated as “The So‑Called KZ‑Syndrome: An Attempt at a Synthesis”. Przegląd Lekarski. 1970; 26: 18-23.

21. Kristal H. (ed.). Massive Psychological Trauma. New York: International Universities Press; 1968.

22. Leśniak R. Poobozowe zmiany osobowości byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego Oświęcim-Brzezinka. Translated as “Post-Camp Personality Alterations in Former Prisoners of the Auschwitz‑Birkenau Concentration Camp.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1965; 21: 13-20.

23. Leśniak R. Zmiany osobowości u byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego Oświęcim-Brzezinka [Personality alterations in former prisoners of the Auschwitz‑Birkenau Concentration Camp]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1964; 20: 29-30.

24. Leśniak R., Mitarski I., Orwid M., Szymusik A., Teutsch A. Niektóre zagadnienia psychiatryczne obozu w Oświęcimiu w świetle własnych badań [Some psychiatric problems associated with the Auschwitz Concentration Camp in the light of personal research]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1961; 17: 64-73.

25. Matussek P. Die Konzentrationslagerhaft und ihre Folgen. Berlin: Springer; 1971.

26. Matussek P. Psychische Schäden bei KZ‑Häftlingen. In Psychiatrie der Gegenwart, 2. Aufl., B. Ill. Berlin: Springer; 1975.

27. Nathan T.S., Eitinger L., Winnik H.Z. The Psychiatric Pathology of Survivors of the Nazi-Holocaust. Isr. Ann. Psychiat. Relat. Discip.. 1963; 1: 113-125.

28. Orwid M. Socjopsychiatryczne następstwa pobytu w obozie koncentracyjnym Oświęcim-Brzezinka. Translated as “Socio-psychiatric After-effects of Imprisonment in the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1964; 20: 17-23.

29. Orwid M. Uwagi o przystosowaniu do życia poobozowego u byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego w Oświęcimiu [Comments on adjustment to post‑concentration‑camp life in former prisoners of the Auschwitz Camp]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1962; 18: 94-97.

30. Półtawska W., Jakubik A., Sarnecki J., Gątarski J. Wyniki badań psychiatrycznych osób urodzonych lub więzionych w dzieciństwie w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych. Translated as “The Results of Psychiatric Examinations of Persons Born, or Imprisoned in their Childhood, in Nazi Concentration Camps.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1966; 22: 21-36.

31. Ryn Z. Uwagi psychiatryczne o tzw. KZ-syndromie [Psychiatric comments on the so-called KZ-Syndrome]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1981; 38: 26-29.

32. Sarencki J. Konflikty emocjonalne osób urodzonych lub więzionych w dzieciństwie w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych [Emotional conflicts in persons born or imprisoned in their childhood in Nazi concentration camps]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1966; 22: 39-46.

33. Sobczyk P., Cielecki A., Zembrzycka-Cielecka M., Krupka-Matuszczyk I., Kaźmierczak B., Łukoszek D. Analiza psycho-patologiczna wstępnego materiału orzeczniczego byłych więźniów obozów koncentracyjnych [Psycho‑pathological analysis of preliminary invalid certification of former prisoners of concentration camps]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1980; 37: 1, 89-91.

34. Sternalski M. Przyczynek do psychiatrycznych aspektów tzw. KZ‑syndromu [A contribution to the psychiatric aspects of the so-called KZ‑Syndrome] Przegląd Lekarski. 1978; 35: 25-27.

35. Szymusik A. Astenia poobozowa u byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego w Oświęcimiu. Translated as “Progressive Asthenia in Former Prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1964; 20: 23-29.

36. Szymusik A. Inwalidztwo wojenne byłych więźniów obozów koncentracyjnych [War disability in former prisoners of concentration camps]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1974; 31: 110-112.

37. Targowla R. Syndrom der Asthenie der Deportieren. In Michel, M. (ed.) Gesundheitsschäden durch Verfolgung und Gefangenschaft und ihre Spätschäden. Frankfurt am Main; 1955.

38. Thygesen P. The Concentration Camp Syndrome. Dan Med. Bull. 1980; 27: 222‑228.

39. Waitz R. La pathologie des déportés. Sem. Hosp. 1961; 37: 1977, 1984.

40. Winnik H.Z. Further Comments Concerning Problems of Late Psychopathological Effects of the Nazi Persecution and Their Therapy. Isr. Ann. Psychiat. Relal. Discip. 1967; 5: 1-16.

41. Winnik H.Z. Second Thoughts about “Psychological Trauma”. Isr. Ann. Psychiat. Relat. Discip. 1969; 7: 82-95.