Author

Piotr Wesełucha, MD, PhD, 1921–1982, internist and psychiatrist, Department of Internal Medicine, Kraków Medical Academy. Survivor of Auschwitz-Birkenau (No. 150107) and Mauthausen-Gusen (No. 3300/45081).

Observations made during internment in concentration camps, experiences from that period, memories that can never be forgotten, camp literature, and the need to express opinions on different – sometimes very delicate – problems with their source in the last war, make the former prisoners reflect on various aspects of life. An example of such a controversial problem which was openly approached based mainly on authentic camp experiences, is the interesting discussion about prisoner functionaries, which certainly did not end with the publication of a report in Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim (Medical Review - Auschwitz) two years ago (Brzezicki et al., 1968). Undoubtedly, it is difficult today to estimate the behaviour or attitudes represented by people imprisoned in the concentration camps without reference to the psychosocial environment of that period. The situation was exceptionally specific, which is why it requires comment.

It is not easy to find a proper comparative structure. In order to understand the essence of the Nazi camps better we may compare their network in occupied territories with the situation of colonial areas that belonged to a metropolis, which were the territories of its policy of expansion and exploitation, and where the interests of the governing authorities were inconsistent with the interests of local inhabitants. Such territories were treated as if they had been a private property of the colonisers and, similarly, the camps were viewed by the SS as such. The owners imposed the political, economic, and administrative systems that would satisfy their needs. The coloniser sometimes allowed for the existence of certain political or social organisations that could operate if they totally accepted the domination of the metropolis, and if they assumed an obedient attitude towards their persecutors.

Only on such grounds were the more ambitious statesmen able to take over administrative offices in the colonial pseudo-country. The country was then governed by discriminating against or favouring certain social and national groups. New social classes were formed. Opportunist local inhabitants were satisfied with a second-best substitute power, which gave them material profits and thus contributed to the process of deepening the extreme poverty of the original inhabitants. The greatest profit, however, eventually had to be transmitted to the coloniser. Through the representatives of his trading and industrial companies (for example, the East India Company), he was able to transact deals that would bring him a one-sided profit. He could impose the development of chosen branches of industry that would be profitable from his perspective, and even if the colony was granted independence in the future, it would not be to able to exist economically without the coloniser’s support.

However, there are countries in Africa that managed to become economically and politically sovereign to a certain degree, after they gained their independence. Such a process is only possible if the country manages to educate a group of its most valuable citizens either in conspiracy or some other way. Some of this group may take up service in the coloniser’s administration to acquire a professional training later used on behalf of their country’s independence. In this way, they possess the proper knowledge and are later able to prevent political chaos in their country.

Concentration camps were a caricature of deformed colonial countries developed “in a test tube.” Among some more obvious analogies, we can enumerate the economic exploitation of the prisoners by the I.G. Farben and Siemens concerns, for instance. The infamous concentration camps associated with those companies were build next to great industrial establishments and called Firmenlagers. It is also commonly known that, for instance, in Monowice, an Auschwitz sub-camp, about 10 000 prisoners did not survive, from over 20 000 working in the factories of I.G. Farben (Setkiewicz, 2001). Even human corpses were used in an economical way, such as attempts at using human flesh and the gold teeth of murdered prisoners.

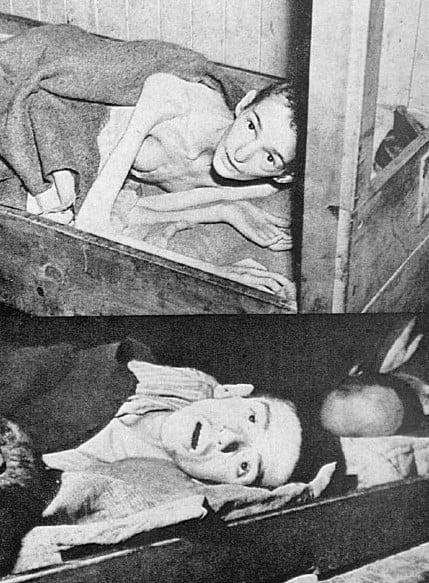

Prisoners in a German Nazi concentration camp

SS forces performed guarding functions; they governed through a very strict control and constant interference in camp life. However, the whole enterprise would have been much more difficult to organise and it would have required many more SS “super-people” if a special system had not been created. It involved the prisoners themselves, mainly criminals and those with antisocial attitudes who were used to organise a governing body that was analogous to that in a colonial country. There was the following hierarchy of positions in that body: the “superior” prisoner in the camp, “superior” prisoners in the blocks, and “superiors” in the rooms. They had an “intellectual” support team that helped them to govern: the camp writer and his assistants, and block writers. Without their contribution, the system of government and extermination of prisoners would have been much less efficient, though it would have been impossible to stop the machinery of mass extermination (such as at Chełmno, Sobibór, Bełżec, and other camps). The officials of the internal camp administration, such persecutors as kapos and their defendants, have repeated that they were “totally innocent”; they “only” obeyed orders. We know such arguments from the trials of the war criminals. To bring the proper contrast to such behaviour, we should remember such a magnificent person as Father Maksymilian Kolbe and many ordinary prisoners or prisoner functionaries who tried to oppose the evil of the camp. Although these are very well-know facts, they should be constantly emphasised. I would like to support the opinions of the late Stanisław Grzesiuk which were presented in his book (Grzesiuk, 1967) and which were met with unjustified criticism because of a too realistic description of the camp life.

As I mentioned above, some prisoners only obeyed orders. There were also, however, those who, in their over-eagerness, did more than they were ordered by the “colonisers.” This must have resulted from specific personality features. The next group was made up of kapos who were the prisoners’ foremen, and supervised their work. If an Arbeitskommando [German “work unit”] included a group of several hundred or more persons, then an Oberkapo [German “superior prisoner functionary”] was assigned to such a group and supervised several kapos, in turn, controlled smaller groups of people. The basic features necessary to be appointed a kapo were a ruthless and inhumane attitude towards fellow prisoners, and the ability to kill “on command,” for pleasure, or just “to keep on training.” I am not speaking, however, of the kapos who were forced to undertake this function and controlled a group of 5-10 prisoners, usually their own friends, who worked as surveyors, tailors, hairdressers, and in other similar professions.

All prisoners who belonged to the hierarchy described above were free from any kind of punishment for additional, “extra,” inhumane treatment of the other prisoners. They were the law, and could modify the regulations to suit their own purposes. They introduced extra taxes on food rations that were equivalent to half of the necessary amount of calories for a prisoner.

An attempt at a psychological understanding of such attitudes is extremely difficult. It might be interpreted as the need to satisfy urges manifested as hunger, thirst, and the need to conserve physical energy. They might result from the self‑preservation instinct or a desire for power. In many persons, such social motives as aggression, domination, and the need to show off could be observed. In others, there was the motive of success, which in a way opposed the need for community. It appears, however, that an explanation is possible only in terms of psychopathology and socio‑pathology, which is probably the most proper approach to such a situation.

Starvation must be assumed to have been one of the basic factors in the camp. When animals starve in laboratory conditions for a relatively short period of time and food is placed behind a partition of wire netting, they go round the partition and quickly find their way to the food. But when animals starve for several days, then they behave pathologically at the sight of food. They jump at the partition, hurt themselves, and are stuck in one place. They are not able to find a simple way to their food. It is astonishing that older phylogenetic centres, including the hypothalamus, take supremacy over the apparently strong cerebral cortex in a very short time.

Man possesses phylogenetic cortical centres that are even younger and weaker in comparison with the archicortex. It requires outstanding individuals with well developed higher needs and socio-centric attitudes to achieve reactions of emotional maturity. Therefore, we, the former prisoners, should not be accused for the fact that we submitted to a situation in which starvation dominated all other factors. Thus, cultivating any patriotic or other “higher” motives was not possible at all in our position. People behaved like a hungry animal stuck in front of the partition, on the other side of which they could see food. Even if the food could not have been seen, there was still the human imagination, which can conjure up anything. When I meet a group of former prisoners, we often talk about those wonderful imaginary feasts, dishes eaten in “imagination and conversations.” My favourite dish I dreamt about all the time, I remember, was not anything exquisite or even bread, but a simple potato. In the “sick‑room” of Birkenau, Apostoł-Staniszewska (1969) dreamt and hallucinated of an ordinary rutabaga and a glass of water. Professor Brzezicki (1963) wrote, “In Sachsenhausen, the thoughts of most of us revolved constantly around food.” For us, a potato or a rutabaga were the most wonderful dream, just as for the Chinese, rice might be such a delicacy.

Thus, starvation was one of the essential factors which motivated all the prisoners’ actions. The ability to adjust to such an abnormal environment led to the stunting of human development.

Fear was another basic factor conditioning the behaviour of the prisoners. It was the constant fear of death, the fear that one might be selected for a group that was to die in the gas chamber or to be shot, the fear that one might be moved to a dangerous Arbeitskommando, that one might be forced to do penal exercises, or “get in the bad books,” as we called it. The camp, full of an atmosphere of constant fear, burdened us with a permanent psychological stress, flavoured with a motive of anxiety caused by personal danger.

People can learn to react in such a way as to avoid fear; such reactions are called defence mechanisms. Some of these were attempts to change to a safer job, and the readiness to join a stronger party that possessed powers of control and persecution. Therefore, many prisoners decided to perform the function of a block superior, a prisoner clerk, a kapo, and thus managed to free themselves of starvation and, at least to a certain extent, of fear.

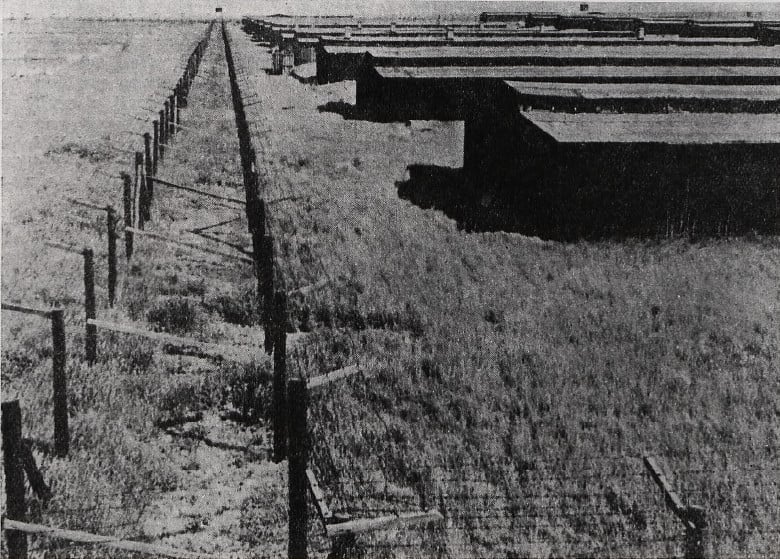

Barracks at the Majdanek concentration camp

Psychological stress resulting from long-lasting fear caused states of inhibition in some prisoners. They became ignorant of all stimuli and it appeared fear did not exist for them anymore. They moved slowly, and did not avoid blows. Their sight evoked an image of the tortured first Christians who, although in a different situation and for different reasons, did not protest when they were being led to death, to be devoured by wild animals in the full sight of crowds who waited to see the terror in the eyes of the condemned and were disappointed by their passivity. I can very well understand apathy as a defence mechanism. It allowed one to remain numb to all stimuli, and permitted internal psychological regeneration. Such an attitude almost always led to a tragic end, though I can recollect cases when that reaction to pressure gave good results.

It was easier for the prisoners to endure the stress if they did not suffer from starvation at the same time. Suppression was the usual defence mechanism then. It enabled the prisoners to survive the most critical period. In contrast to block superiors, prisoner clerks or other “rulers,” however, prisoners who no longer starve but are still exposed to fear, despite that defence mechanism, even these days are “afraid of their dreams,” as Półtawska described it in her recollections from Ravensbrück.

Many prisoners were not able to stand the permanent fear, and their reaction was escaping to death. They usually flung themselves on the electric wires to find the long‑awaited peace. When some specific events became a source of stress, the degree of negative pressure and tension depended on their psychological resilience and the meaning a given person attributed to the stress. From the physiological perspective, the sense of danger is essential. The result may be the breakdown of the homeostasis of the organism that constitutes a complex dynamic system, the balance of which may be easily destroyed. Thus, it was only natural when all defence mechanisms failed, that suicide, more often than not “successful”, was frequently the last resort.

It is well known that the structure of the concentration camp, designed by the SS with deadly efficiency, served the aim of a precise and total extermination of the worthiest human beings. This was carried out mainly by the SS “super‑people,” who, to make their job easier, provided the prisoners with a kind of a colonial‑like autonomy, left in the hands of those who decided to cooperate with them. Such prisoners, as stated earlier, were usually antisocial psychopaths, who wore green or black triangle badges.

The “green,” who were incorrigible criminals and could not be re‑socialized even by lengthy prison sentences, found special pleasure in torturing their subordinate fellow prisoners.

The “green” were usually lazy, they lied and had no friends. Almost all of them had no moral restraints whatsoever; all of them were intellectually obtuse. There were hysterical psychopaths among them, although it would be difficult to define any distinct forms since these people had different psychopathic features, especially those of despotic psychopaths (gemütlose Psychopathen, to quote the term used by Schneider-Cieślak et al, 1968). The “green” wanted to impress those around them, tattooed themselves in an extremely sophisticated manner, were frequently punished for fraud, for pretending they were important persons, or for living on the earnings of prostitutes.

As well as the antisocial and hysterical psychopaths mentioned above, an important role was played by impulsive psychopaths who could murder in a fit of rage, in contrast to the previous group who murdered only after a “careful consideration.” This group behaved according to their own “law.” They ruled according to the most brutal habits of criminal underworld and gained approval and compliments during roll calls from the Lagerführer [German “Camp Leader”] himself. In Gusen I heard myself the Lagerführer express his dissatisfaction with the too small number of deaths, which made his “green” prisoners very unhappy. Still, he liked them a lot and was even willing to make some concessions to them. Still, they suffered despite the fact that they could fully satisfy their hunger and could provide themselves with, at least partial, security. They were almost free from fear but despite this, they still suffered.

One of the oldest phylogenetic parts of the cerebral cortex (archicortex) is the sexual impulse, and the “green” could not satisfy it in any natural way in the camp conditions. They used all sorts of substitute means. One of the basic ones was paederasty, but the “greens” valued themselves, and so forced others to choose new attractive boys with effeminate features for their deeds. Some grasped this chance and helped the “governing circles” to satisfy their sexual needs, initially for bread and later to obtain some power or for their own satisfaction.

In the period when discipline was not very strict in the camp, they would organise the so-called buzerantenbale in Block 20, or in one of the neighbouring blocks. Certain prisoners from the camp would gather there, an orchestra was invited and paid in food and cigarettes, and they danced exciting tangoes by subdued light. The fact that people were dying in the same block added some piquancy to this scene.

The problem of sexual drive in the Nazi camps might certainly constitute a subject of a separate scientific study. Here, in a short post‑camp reflection, it is still worthwhile mentioning that the majority of the prisoners were not only unable to perform any sex-related activities, but could not even think about them during their entire internment. Starvation alongside with total physical emaciation was one of the reasons; long-term psychological stress was another.

I would still like to return to the analogy mentioned at the beginning, and emphasize the fact that in colonies the most morally sound human beings disable the proper functioning of the machinery of repression through their activities. Similarly, in some camps such as Auschwitz, Austrian and German communists, who were brought there from other camps, impeded many criminal actions of the SS.

Władysław Fejkiel and other Auschwitz prisoners wrote that their most important aim was to save as many prisoners as possible from the gas chamber. When, in autumn 1942, the strictness of the camp regime decreased, an international underground organisation of prisoners was formed by the Austrian and German communists in his “sick‑ward.” They had their headquarters there, and collected information about contacts with the outside world (Hołuj, 1968). Similar underground organizations were also formed in other camps, all of which had similar purposes.

For instance, in Gusen the purpose was to save at least some prisoners from the planned extermination. The underground organisation was very active at the time of liberation. Several minutes after the gates were opened, armed prisoners, members of the organisation, guarded the camp gates, watchtowers, and took over all the important functions. In that way, they prevented a potential return of the SS-men, and managed to keep all the prisoner-criminals in the camp and hand them over to the law.

When I remarked on the situation in colonies, I mentioned the fact that they were exploited economically as much as possible. The structure of the camp was also based on slave labour. Trailers were pulled by emaciated prisoners, and huge boulders were carried on prisoners’ backs over large distances. Such a system of work resembled the way the Chinese built an airport during the last war, which was described by the famous pilot Urbanowicz. Several thousand people were carrying baskets full of sand and gravel on their backs to the place where the airport was to be built. And it was built although there were no machines there and only primitive methods were used.

In Gusen the prisoners put the quarry into use, and hewed hundreds and thousands of impressive stones that were to be used in various construction projects. They were forced to work on the production of Messerschmitt planes and automatic pistols and guns at the Steyr-Daimler-Puch A.G. factory. Nobody asked them whether they wanted to work there or what their qualifications were. Higher intellectual level usually disqualified the prisoner in the eyes of his persecutor. The hitherto existing social hierarchy was paradoxically reversed. It was convenient for the SS that the most important positions were taken up by criminals and murderers who were deprived of human feelings, evil, and indifferent to the misery of others. From a psychiatric perspective, it was a collection of various psychopaths, though this term does not excuse their behaviour. Outstanding people, scientists, administrators, political and social activists and other prisoners with desirable personality features were assigned to emptying cesspools and carrying boulders, and suffered terrible humiliation in their state of starvation.

The observations presented above, my own experience, and conclusions of many other articles and reports made both in the camp and in the post‑camp period, undoubtedly justify the opinion that the whole Nazi lager was an experiment which should be defined as pseudo‑medical. It would probably be naive to compare this experiment to the cruelties performed by small children towards insects or mosquitoes, or when they catch and strangle birds, torture cats, throw stones at dogs playing in the street to see how they slowly die in pain and misery. In the camp reality, the experiment was carefully premeditated, with all the necessary organisational forms, and with full awareness of the far‑reaching extermination purposes. Under those conditions, even if some prisoners managed to avoid the pseudo‑medical experiments proper and survived the camp, they still should consider their stay there as vegetation being a part of a permanent experiment.

Starvation was one of main elements of the experiment planned beforehand, and it usually led to death through different somatic and psychological deficiencies. Prisoners were usually not able to survive the Nazi camps. Beside starvation, they were exposed to constant fear. Maximal humiliation of human dignity, as well as extremely heavy work, lack of medical care, deliberate activities, both criminal and common, aimed at subjecting the prisoners to pain and death, clothes that did not protect from the cold, rain, frost, and snow, imprisonment without a time limit, isolation from the family, living in an incessantly crowded space, and, additionally, the pseudo‑medical practices of SS doctors, were all carefully planned elements of the experiment.

Adapted and translated from Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1970.

References

1. Apostoł-Staniszewska J. Wspomnienia z Brzezinki. [Recollections from Birkenau]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1969;26: 133-134.2. Brzezicki E. Socjopsychopatia a „Kazet-Lager” Sachsenhausen. [Socio‑psychopathy and KZ‑lager Sachsenhausen]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1963;19: 77-83.

3. Brzezicki E., Gawalewicz A., Hołuj T., Kępiński A., Kłodziński S., Wolter W. Więźniowie funkcyjni w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych. Dyskusja. [Prisoner functionaries in the Nazi concentration camps. A discussion]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1968;25: 253-261.

4. Cieślak M., Spett K., Wolter W. Psychiatra w procesie karnym [Psychiatry in legal proceedings]. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Prawnicze; 1968.

5. Grzesiuk S. Pięć lat kacetu [Five years in the KZ‑Lager], 4th ed. Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza; 1967.

6. Hołuj T. The Unknown Anniversary. Polityka. 1968;21: 1 and 11.

7. Setkiewicz P. The Histories of Auschwitz IG Farben Werk Camps 1941-1945. Oświęcim; 2001.